Visual Scripting

In this blog post we’ll cover some of the basic ideas behind the design of Boardgame Lab’s Visual Scripting language. This is by far the most ambitious aspect of the project and something that has been on the drawing board from the very beginning.

In a nutshell, we’d like everyone (including non-programmers) to be able to create implementations of board games that are scripted to various degrees. For some that might just mean automatically shuffling decks at the end of turns and automatically drawing cards to player hands. For others, it might mean full rules enforcement for an app-like experience where the game takes care of everything including scoring.

Why Visual Scripting is hard

There is a reason why textual programming languages are more popular that visual alternatives. There is a whole ecosystem of software like debuggers, version control and text editors that make it much easier to work with textual programming languages.

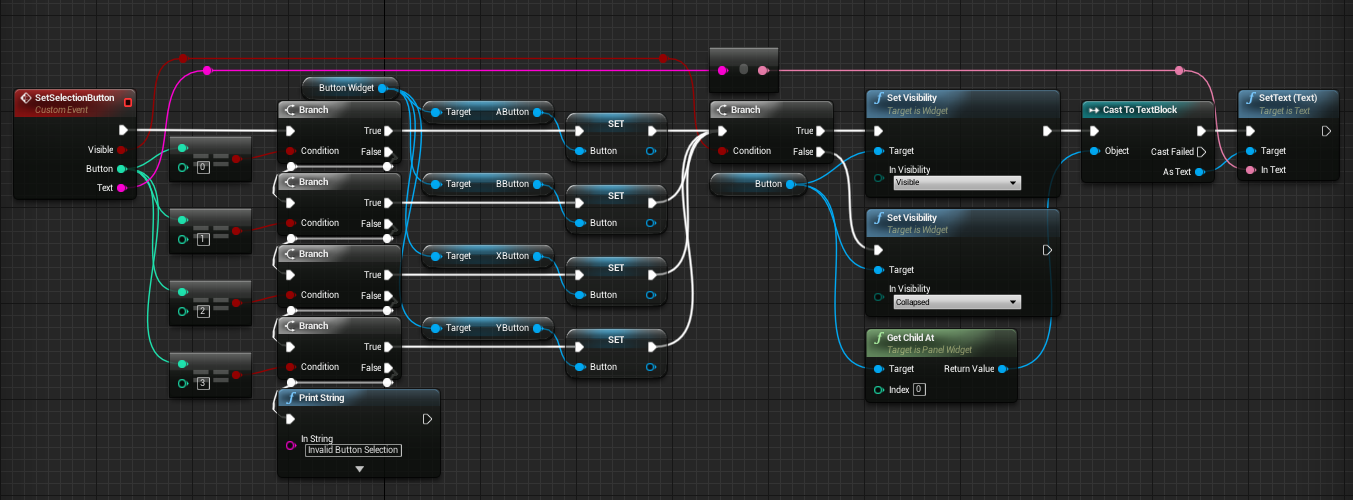

Visual programming, on the other hand, tends to be clunky, less expressive and hard to debug. Node-based (or graph-based) approaches in particular are prone to a visual messiness that make it hard to understand the logic being expressed.

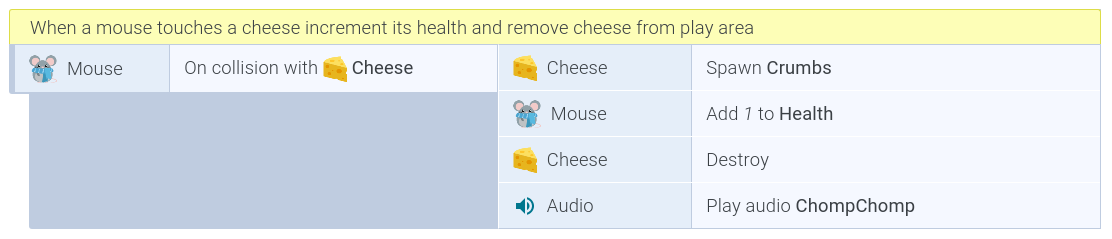

The other prominent visual paradigm is a block-based approach. These are often neater than their node based counterparts. This is used to good effect in Construct 3.

Boardgame Lab’s approach

Boardgame Lab incorporates elements of both node-based and block-based paradigms. A rule is assembled as a series of expressions, an expression being something that evaluates to a value.

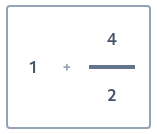

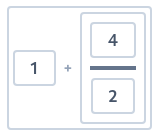

For example, the following expression evaluates to the number 3.

A closer look at this expression reveals several nested expressions. The innermost expressions containing the actual numbers are called literals. Literals are expressions that just specify the value that they produce directly.

The evaluation of an expression proceeds by methodically replacing inner expressions with the values that they produce until the outer expression’s value is finally produced.

Actions

Expressions that produce values seem like they might be useful in a calculator app, but how are these relevant to board games? The answer is that certain expressions also have side-effects as they are evaluated, including the ability to trigger actions on the board.

If the expression is part of a rule that is attached to an object, then the actions within the expression affect that object by default, but they can also be configured to act on other objects on the table.

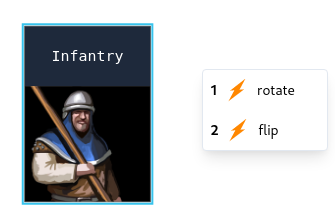

For example, cards have a rotate action that rotates them by 45°. This can be triggered by clicking on the “rotate” action after selecting the card in the Play area.

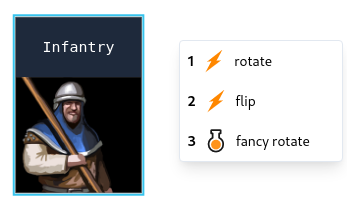

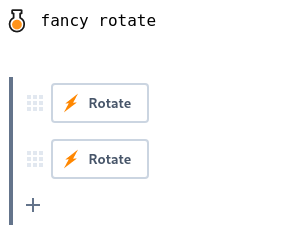

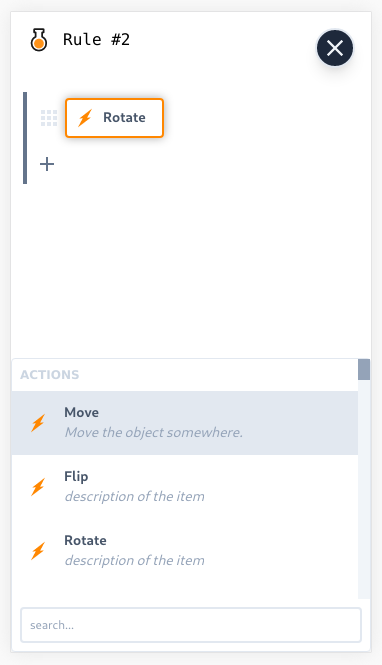

We could also create a rule called fancy rotate with the following content that would do the same thing:

The rule contains a single “Rotate” expression. This expression is an action expression (signified by the lightning icon). It produces an empty value, but has a side-effect of causing the object it is attached to to rotate.

The rule is triggered similar to the way an action is performed on the card. Just click on the card and select the rule.

If we added another “Rotate” expression to the rule, then the object will rotate by 90° when the rule is triggered.

Expanding Expressions

Creating rules that are just a list of action expressions can only get you so far. Eventually you will want to wrap simple expressions inside more complex ones to unlock the real power of rules.

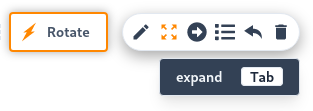

To expand an expression (i.e. wrap it inside another one), click on it and then click on the “expand” tool (or press the Tab key).

This will bring up a menu where you can select various expressions that you could wrap this expression in.

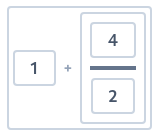

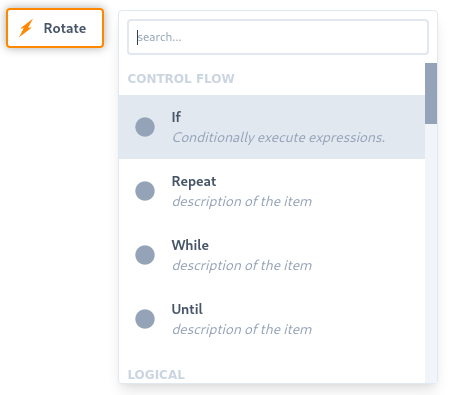

If we choose the Repeat expression, then our original expression gets transformed into this:

As we can see, the Repeat expression contains two nested expressions. The one on the left (which is initially empty) must produce a number, which is the number of times the expression on the right side is executed.

We can simply replace it with a literal 4 to perform the rotation four times.

We could have also replaced it with a more complex expression that results in 4 and it would do the same thing.

That’s the beauty of expressions. An expression like Repeat is not limited by forcing you to type in a number. You can produce that number using an arbitrarily complex expression. For example, you can create an expression that counts the number of yellow cards on the board and use that as the Repeat parameter.

Let’s take a look at all the nested expressions in that last expression just for reference:

Pipes

The other way of expanding an expression is to pipe it. A pipe is a conduit that transports the value produced by one expression to another expression on the right. The expression on the right can subsequently also pipe the value further along to create a chain.

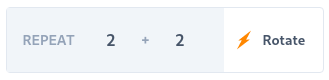

To create a pipe, click on the expression and then click on the “pipe” tool (or press the | key).

The expression now feeds its value to a new (empty) expression.

If we replace the empty expression with a property attached to the object, then the value 10 gets written to it.

If we replace the expression on the left with health + 1, then this has the effect of incrementing the health property.

Eventually you will be creating more complex pipes that can describe game situations like buying a card.

Supporting different modes of working

A common deficiency of visual scripting environments is that clicking and dragging things quickly becomes cumbersome when trying to implement a sizable piece of logic.

One of the key design features of Boardgame Lab’s Rule Editor is that it can be used completely from the keyboard. So, you can effectively “type” your way through an entire rule and work much faster than you would be able to if you had to click and select things.

Try a preview of Boardgame Lab today by joining our Discord server!